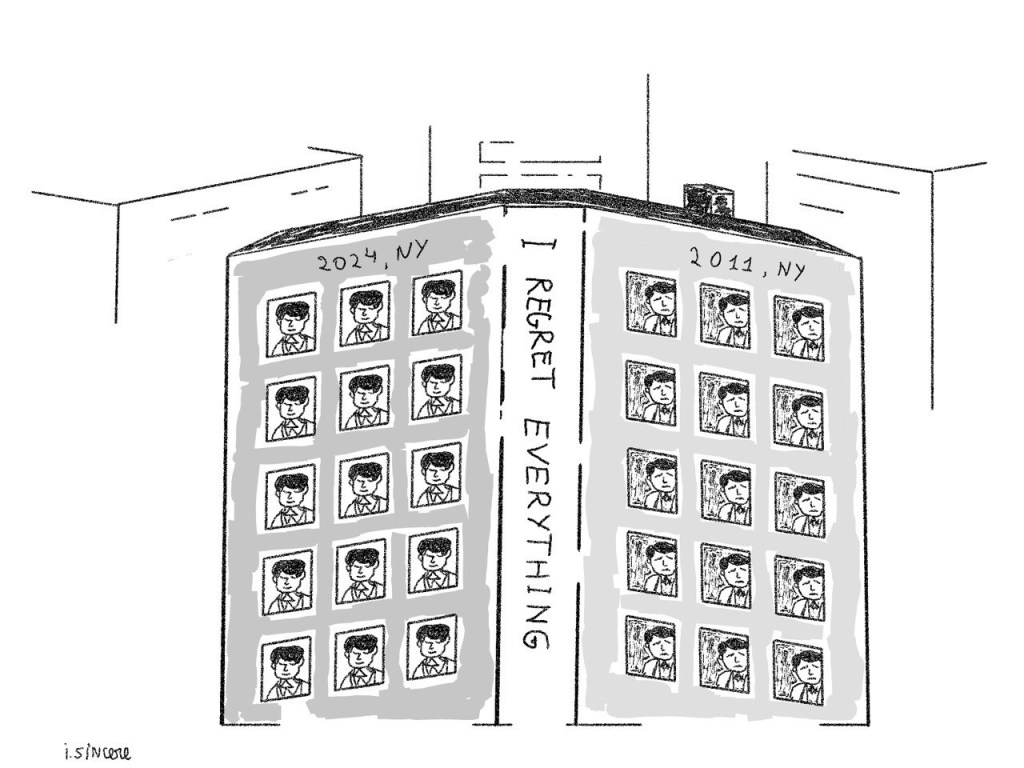

Earlier this year, I was walking the streets of New York, drifting between coffee shops and small stores, just enjoying the city. I couldn’t help remembering my first time here in 2011, when I had no money and ended up sleeping on the streets with the Occupy Wall Street crowd. I didn’t even know what their agenda was. I had a cheap Nokia phone and no internet. For three nights I slept beside random anarchists and every morning I ate five-dollar pancakes. It sounds miserable, but I was happy. When you’re twenty, the world feels wide open.

Now in my thirties, I came back with a different hunger. This time I wanted to taste New York properly, the food I couldn’t afford back then. A few people I met at the exhibition invited me to dinner at Balthazar. The place had been on my list for years. Walking in, I was struck by the light, the way the colors and space held together. You could tell someone with real taste created it.

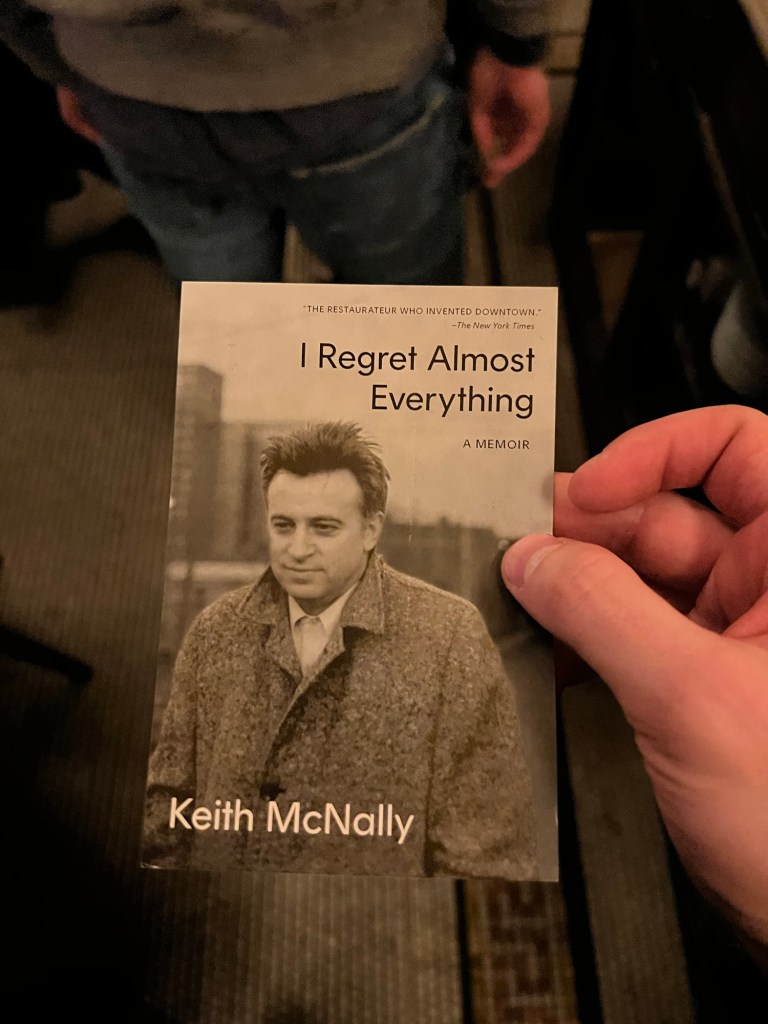

What I didn’t expect was that the man behind it was there, sitting a few tables away, presenting his new book. The title: I Regret Almost Everything. I picked up the post card and saw his photo – a young, scared man in black and white. It pulled me back to my own 2011 self, broke and wandering the city but happy with how things are anyway.

Orson Welles once said in an interview: “I can’t understand someone who has no regrets.” He looked uneasy when he said it, like the words were hard to admit. I agree with that statement, regret is what makes us human. That sentence came back to me as I opened McNally’s book later at home.

The book isn’t the usual memoir story arc. Not the boring pattern of born, suffered, grew stronger, succeeded, died. McNally writes about success, yes – the restaurants, the travel, the family but every page is soaked in regret.

Even his obsession with art. At one point he says, “Given the choice between spending money on a good school for my children or an oil painting by Max Pechstein, I’d spring for the Pechstein every time.” That kind of line tells you everything. Surrounding yourself with art like it’s a lifeline, but knowing it costs you something else.

Then there are his films. His big dream. He made two. But by the end of the book, you feel him admitting they mean almost nothing. Just another obsession, hard to care about compared to the restaurants. I find that funny, but also true. We all know chasing dreams can give you nothing.

What stays with me is the contradiction. The same man who created restaurants where people connect, eat well, enjoy themselves – he couldn’t find peace in his own life. The person giving happiness to strangers is himself deeply unhappy.

He also reminds me of one of my favorites, Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night. Celine escaped the war, McNally escaped his family, his community, the poverty of London. Different reasons, but the same kind of voice full of contradictions , the same obsession with regret.

At one point he writes (I think it’s similar to Celine cynicism):

“The worst thing about dying is how easily life goes on without us. Garbage still gets collected. Lawns continue to be mowed. Elections still get held. No matter how monumental my death was to me, for the rest of the world it would be, at best, a faint murmur.”

This one also one of my favourites:

“Getting married is like boarding a train without knowing its destination. I thought my train was heading for Kansas. Who knew it would end up with a leather-coated SS officer serving me divorce papers in bed?”

Anyway. I thank McNally for the delicious steak and wine at Balthazar, but even more for the monument of regrets he left behind.