We didn’t plan to go there really it was our first time in Edinburgh and exhibitions were not planned. We just saw the poster by chance – cracked clay like drought, strange and quiet. “Andy Goldsworthy, 50 years in making” – the name felt familiar, though I couldn’t say from where. Trainspotting? – I thought – no, that was in 1996… Maybe from some documentary or art book, something in the background of my memory. I assumed it would be mostly photographs, and I said to Alina that it will be super boring to attend (I should stop using this word I hate it so much).

We walked in, and within seconds I knew I’d been completely wrong and this will be “the place of power” as Kastaneda would say and most likely I will be a completely different person after this. I was not wrong.

The first room was a corridor of branches, densely packed, rising waist-high on either side like walls made of tangled bone. Neatly arranged, geometric but still wild. Not decorative, not pretty – more like a structure nature might’ve made on its own if it cared about symmetry. I thought we were about to enter a garden?

That’s when something started to shift. Not in the work, but inside me. The idea of garden, and simple natural objects reminded me my childhood desire to organise sticks, or, finding _the best ever_ stick in the woods.

I kept thinking about gardening and what it means to me as we walked farther. Not as a hobby, but as a form of composition. It’s one of the few crafts where the material has its very strict timeline and main constrain is that you can’t fully control it. You guide it and it grows back in its own way. Same with Andy’s work– it doesn’t try to dominate nature, it simply follows it, listens to it, sometimes just frames it so we can see it better. Just like these branches or leaves followed the shape of the fallen tree:

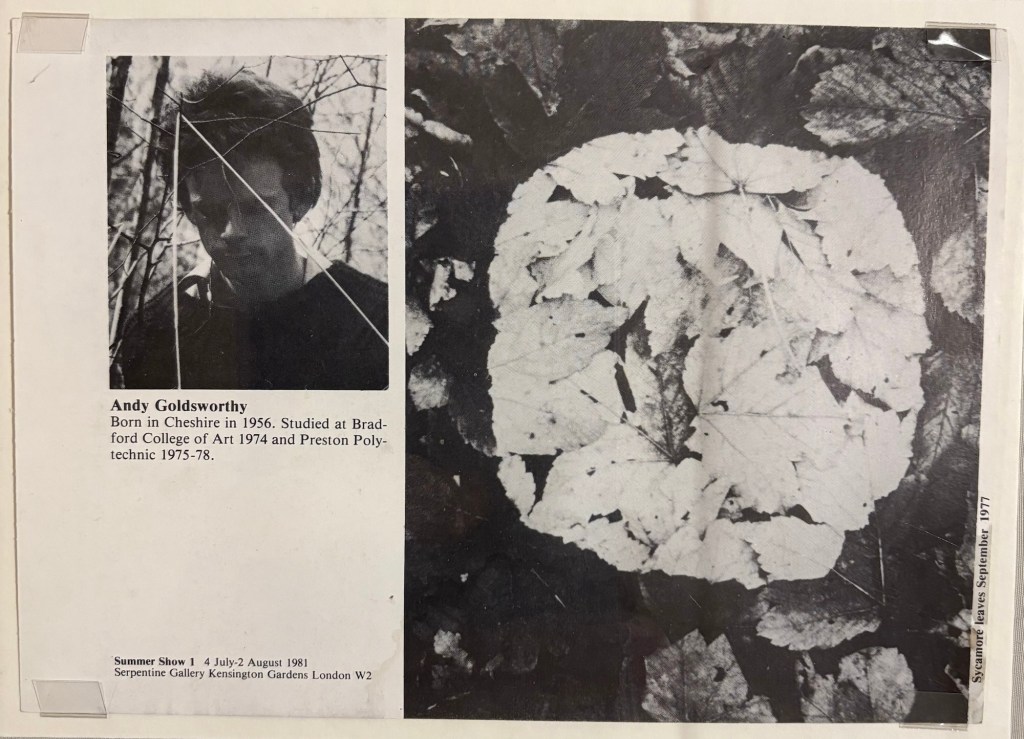

Later I found out he worked on a farm when he was young – full days of manual labor, out in the weather, no shortcuts. That made sense and answered on many why’s. His work isn’t mystical, I thought immediately, it’s predominantly physical. You sort of get the weight of time in it, you need to be patient and precise in order to create these works but never fussy. There’s no fantasy in it or a dramatic story, or some philosophical sense either quoted paragraphs from Deleuze. It’s very simple language: leaves + patience = composition:

I worked as a gardener once, back in 2014 near the Forest of Dean. Andy reminded me about this fantastic experience. I remember the slow transition from autumn to winter. The way decay took over everything – yellow leaves turning brown, the first frost hardening them like paper sculptures. I remember wanting to shape those moments somehow, to keep them. I had no tools, just the impulse to notice. Andy didn’t just notice – he turned that impulse into a practice.I’m pretty sure leaves his main inspiration, but I couldn’t find confirmation… except this little note from his early works:

Coolest part – is Andy’s snowballs! He once brought snow into London. Picked it up from the countryside and placed it back into the city, carefully arranged on pavements and street corners in the middle of summer. No signs, no explanation, just sudden little ghosts of winter melting quietly into the heat. Not performance, not protest –something more subtle, more absurd. It made you stop, wonder what you were seeing, question what month it was. I think it’s one of the most brilliant pieces I’ve ever come across.

It made me think – this is what art could be for everyone (like, an industry or something – not just niche), if we stopped trying so hard to make it into something grand.

That’s what struck me most, actually: Andy doesn’t make nature into art, he reminds you that nature already is art. That the world is full of forms and rhythms and beauty we barely pay attention to. His language is made of sticks, leaves, mud, snow, rain. There’s no invention in it, only recognition.

I walked out of that show feeling quieter, slower, different. I hated myself for chasing ideas or ways of making things, searching for novelty, trying to invent something worth saying. But Andy made me realise that the main event is already happening.

The world is sculpting itself every minute. We’re just too distracted to notice.

Thank you Andy for showing me that collecting leaves for fifty years might be more radical than anything new.