There’s a particular silence that lives in the desert. It’s not empty, it hums. Michael Heizer listens to that silence. Then he cuts it open.

Heizer is one of the most uncompromising sculptors of the last century, though “sculptor” feels too ornamental, too safe. He doesn’t carve, he erases. His works are not objects but events, not additions but subtractions. Where others build monuments, Heizer removes the earth itself.

After reading the book Sculpture in Reverse, something clicked. Heizer isn’t just an artist – he’s a rupture. A gap in art history where meaning leaks out and something new, or ancient, flows in. He doesn’t decorate the world, he subtracts from it.

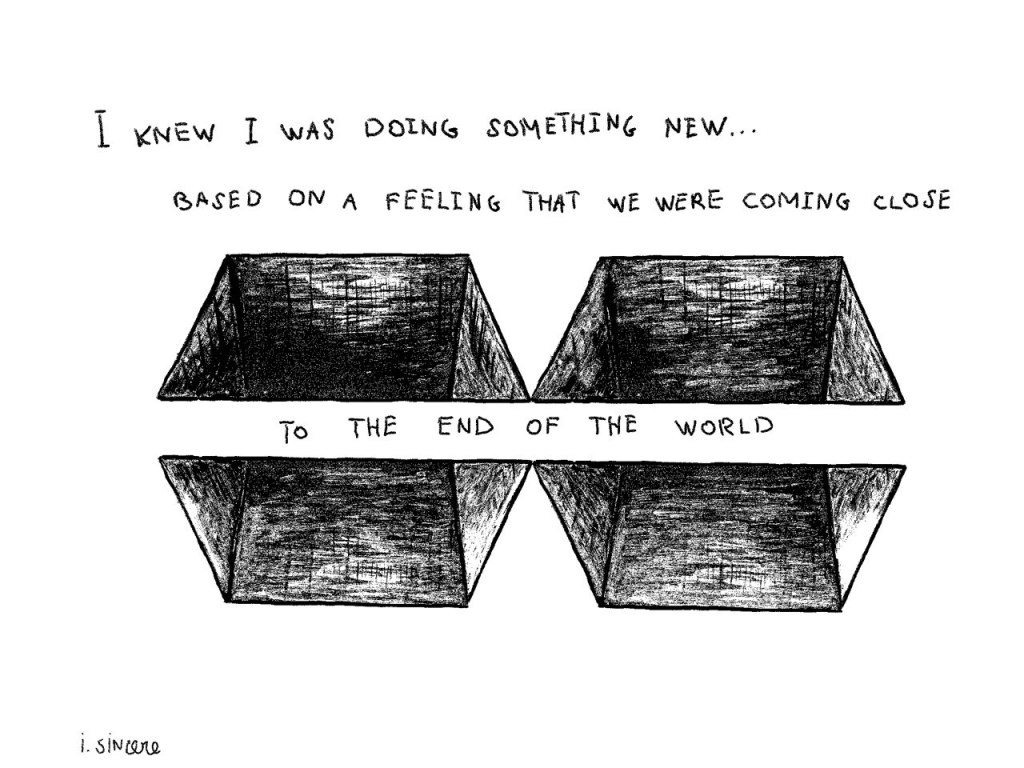

“I knew I was doing something new… based on a feeling that we were coming close to the end of the world.”

He’s not melodramatic, just precise. Art after Hiroshima is not the same. It can’t be. We live in a nuclear era, and as Heizer says, a schizophrenic one – technological and primordial at the same time. We still have Stone age minds, but we carry satellite devices and global dependencies. Heizer’s work reflects that fracture. He ran from the city to the desert, away from glass towers into holes in the ground.

“My original impetus for getting out of the city… had to do with the idea of the insecurity of society, the frailty of its systems, the dependence upon interdependence.”

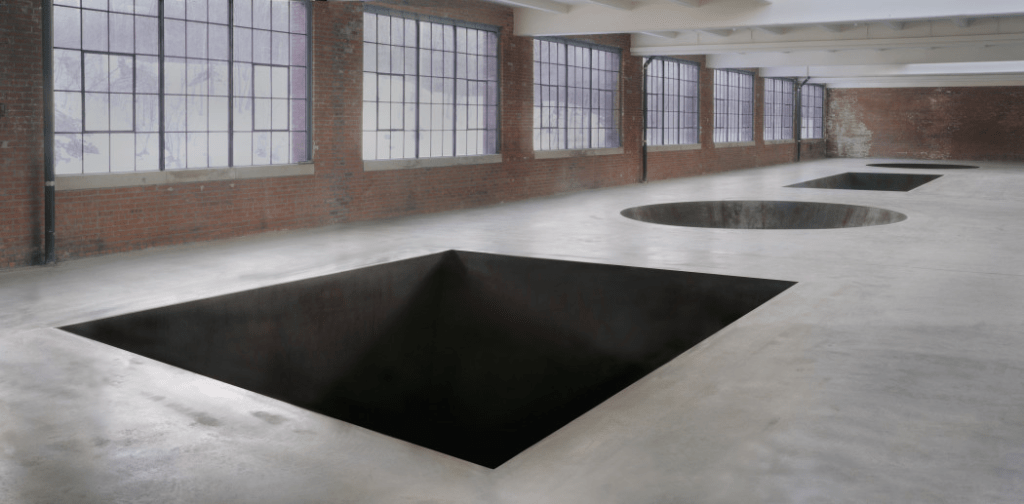

This isn’t land art for aesthetic pleasure, I believe it more an existential excavation. His most famous piece, Double Negative (1969), is not a sculpture but a void – two massive cuts carved into the Mormon Mesa in Nevada, 1,500 feet apart, created by removing 240,000 tons of earth. There’s nothing there. And that’s the point…

“There is no indication of why they are there, or what happened to the voided material… It was made using its own substance.”

That phrase “its own substance” could define all of Heizer’s practice. He doesn’t really shape the rock, he honors it. He uses 30, 52 or even 68 ton stones not to impress but because they carry weight – literal, conceptual, mythological.

“A piece of rock can be a sculpture… you don’t have to design it. I want the thing to have power so I find something that has power.”

This power is primal. His materials aren’t modern – they’re before modern. Pre-language. Pre-thought.

“A piece of rock in exchange for all that. What carries it? Massive weight… We have returned to a primitive stage.”

He’s obsessed with American art – not in a nationalistic way, but elemental. He rejects European art tradition: “paintings on canvas and sculptures you walk around that look like Balzac or Moses.” I couldn’t agree more with that statement. Especially modern art with all these art supplies stores full of plastic paint and polished canvases. Instead, he aligns with South American, Mesoamerican, North American traditions – earthworks, ritual, monument, natural materials only. Back to the roots.

His magnum opus, City, began in the early 1970s and spans over a mile in the Nevada desert. It looks like an archaeological site from a future that never happened. It’s not a city, but a fossil of civilization, a eulogy to architecture.

“It is a reversal of issues… the earth itself is thought to be stable… I have attempted to subvert or at least question this.”

Each form in City, like Complex Two, sits half above, half below the ground. It’s hard to even see it without entering it. It refuses to be known from the outside. A structure that looks inward.

“It’s a complex that faces itself… there’s only one way to see it, and that’s from inside.”

What I really appreciate about him is that his philosophy is anti-spectacle. No Instagram angles, no narrative hooks, no spicy installations. Just confrontation: human vs rock.

“There are many limits to what can be done with rock. It fights back.”

That’s the confrontation I keep thinking about.