My obsession with Cioran started in my early twenties, when, like most teenagers, I found his Journals. This moment changed my life completely, making the intro to my ability to align with the feeling of despair, cosmic pessimism, suffering.

I experienced a real connection to everything Cioran wrote. I have never tried to read these Journals again, and at this time in my life, I don’t even remember any more quotes.

I only remember the feeling I had when reading it – a very strong connection about the most important things in life.

Later on, I started meeting people who loved Cioran. I started using him as a connection point to make new friends, because anyone who had read Cioran and digested this pain would automatically mean they were like me. I met a few wonderful friends, and we all talked about Cioran from time to time, mainly having a few cioranian jokes or a few cries about suffering at the bar. We mainly talked about him as a figure and how he denied life, but not his writing, which I think is interesting to note.

I didn’t know his full biography, only watched the documentary about him a few times “Apocalypses according to Cioran”. This film added a few more details I didn’t know but also showed him as I imagined through his writing: quiet, depressed, sad, melancholic, slow, dark-humored, lonely.

I fell in love with him deeply. I started becoming him in a way. Especially after reading more works, especially The Trouble with Being Born. Like Cioran, I denied life, denied having kids, started denying almost everything I touched. I have carried a few quotes from the book with me in my pockets, like:

“We are born to betray life, to disown it. We are born with a nostalgia for nothing.”

My life movement and trajectory somehow changed just because of his writing and his view on the world. At my 30s, I started feeling weird about it. Should I project my life onto his so badly? Should I learn more about his life, so I could understand what I’m dealing with? What is even happening? I dropped the idea of learning tiny details about his life and going deeper into the archives. My life got complicated enough, and I switched my obsession to a few other writers and directors, and started projecting onto them instead.

Sometimes, I would be honest with myself and think:

“I want to write something — I think it should be a dark satire, but also have a bit of Cioranian worldview in the style.”

or

“Today is my birthday. What if I go to a cemetery and film something with quotes from Cioran? That would be awkwardly beautiful.”

I kept adding Cioranian honey on top of my cereal-like morning writing.

***

A few years later, I am finally in Paris, walking through Montparnasse Cemetery, holding his Journals (but not brave enough to read them through again!). The rain hammering me and the surroundings, dripping from old black trees and stone crosses. I keep walking to his grave, struggling to find where it is.

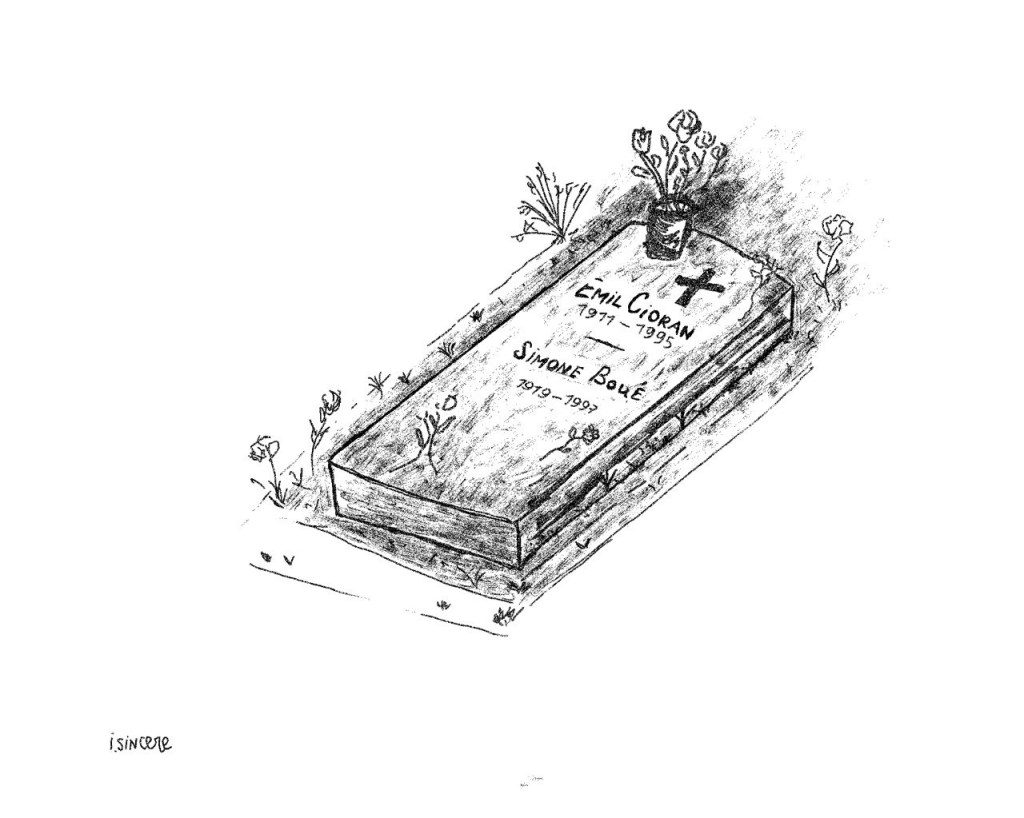

Oh, here we are – a small, tiny grave, like his apartment, and his not modest life. The stone is cold and plain, beads of rain rolling down the engraving like tears. Romanian flag, a few flowers. Wow, how great to be here. I kneel and put a few rough rocks on top of his name, feeling the dampness in my palm.

Wait. There are two people buried here. Who is Simone? I don’t remember. Ah, wait, I’ve heard about her. She is his lifelong friend, I remember. I am not sure why I didn’t dive into reading about her. I don’t remember reading about her in his Journals. Typical Cioran: not exposing his life and loved ones to the crowd. Rain annoyed me and I walked away.

I kept thinking about Simone. Coming back to the hotel, I figured out a few interesting things.

Simone was his partner, not friend. They met in the late 1940s after Cioran moved to France from Romania.

“Wow, the WWII just began!” – I thought.

Cioran lived in poverty at the time when they met. Simone became both a companion and a pillar for him: she provided stability, a home, emotional care. She worked while Cioran spent much of his time writing and wandering.

“What a privilege” – I thought immediately!

They never married.

“That makes sense, Cioran despised institutions like marriage and saw it as a trap” – I quietly nodded.

They never had children.

“Also makes sense, Cioran thought bringing children into this world was an act of cruelty.”

They lived together for decades, but Simone kept a low profile – no public declarations, no coquetry.

“Right, now I got why I didn’t know about her.”

But also this discovery frustrated me. Does it mean that Simone accepted his darkness, his constant pessimism, his long periods of illness and depression and just supported him all the time? What an act of love. A quiet agreement.

I got out from the hotel and went for a walk. The parisian light and magical music everywhere calmed me down a bit, and started reading more about Simone. I discovered a very important detail:

It was Simone who preserved and published his Journals.

So, without her, there is no Cioran for me. Without her, I would not have been carrying that battered book through my whole life. But most importantly without her, much of Cioran’s real voice would have been lost.

***

I wanted to see the place where they lived in Paris – 21 Rue de l’Odéon. I wanted to explore the surroundings. Interestingly, they had one room, very little furniture. Cioran had a rickety desk, a mattress, and piles of books. They didn’t even own a refrigerator until very late. Cioran insisted on living poorly, believing comfort weakened the soul.

But I was not sure if Simone accepted this minimalist life without complaint? The image in my head was intense: two people, quietly enduring Parisian winters, no luxuries, no comfort, only survival and silence.

While drinking coffee close to their apartment, I found more things about this weird couple:

Simone translated one of Cioran’s books into English – but anonymously.

They took long walks – sometimes speaking very little.

When Cioran fell ill, Simone refused to institutionalize him. She cared for him at home personally until it became physically impossible.

After Simone’s death, her brother burned many of her personal papers. As a result, we have almost nothing left of her voice.

So Simone wasn’t just “Cioran’s partner.” She was his co-sufferer, his shield, his silent twin. She took care of life’s small but necessary things (contracts, logistics, money issues) without ever pushing herself into the spotlight. So important findings, I thought.

And cherry on top – the comment from Cioran’s publisher Antoine Gallimard:

“Simone handled all practical matters with discretion and intelligence, leaving Cioran free to cultivate his despair.”

In sum, people surrounded Cioran admired Simone deeply, but almost always with this tone of awe, because her way of being – invisible, silent, self-effacing was so rare, especially in a world full of loud, ambitious, competitive intellectuals in Paris. She lived exactly in the margins, just where Cioran, the great poet of the margins, needed someone to be.

I liked her. Especially her smile on this photo:

And I started disliking Cioran slightly, I couldn’t articulate why. I went to explore other parts of Paris, and stopped thinking about these two and their strange life, which I didn’t quite understood. The last question appeared in my mind was actually about Simone:

Why Simone’s brother burned everything? To protect her privacy or maybe because he thought they were insignificant?

***

In the evening, I went to a bar and was drinking a loooot. The windows fogged with dampness, and my shirt steamed in the heat. Why it’s so hot in first days of May? I met some weird architect who gave me some guidance on what to drink and ordered really ugly thing for me to try. I forgot to ask him about Cioran and Simone! A few hours later, French guys in jackets came in and started a conversation. Two of them were teachers – one taught law, the other history. I asked them what they knew about Cioran.

“He is one of the all-time favorites. He wrote in French and lived in a tiny apartment in Paris,” they said.

Yes, I know that, I replied.

But do you know anything about Simone?

“Debovuar? Sartre’s wife?” one said.

No, I said.

Cioran’s wife.

They didn’t know.

I ordered more drinks and started reading more online. I found more photos of them together. I assumed more strange things: perhaps neither Cioran nor Simone seemed to seek happiness from each other? Instead, they shared something deeper – a life anchored in a mutual understanding of existence’s bleakness? I could relate to it. I searched through the Journals again, hoping for something about Simone, maybe just a line or at least something like this:

“Simone just brought home kefir. I don’t like kefir. It makes my stomach bloat like cosmic dust in the Oort cloud.”

But there was nothing! Not a word. And nothing in any interview. The only quote some readers link to Simone is:

“The only being whose existence has prevented me a thousand times from committing suicide, whose presence alone justifies a compromise with life.”

Just this quiet, tiny acknowledgment. I started feeling dizzy. The French guys who earlier seemed friendly now started annoying me.

I went outside for a night walk, a frustrating thought appeared again and grew: I think I found the most important detail about Cioran’s life, and I can’t tolerate it, I can’t continue feeling connected with his works.

Essentially, on the surface (publicly, for losers like me!), he sold the image of total solitude, despair, radical honesty, deep understanding of suffering. But privately, he relied on Simone deeply and quietly for survival (for 50 years). She protected him from the real struggle: working shitty jobs, begging, selling out. The kind of life for example Henry Miller lived in full: stink, sweat, dirty Paris streets. Or Bukowski? Or any other writer?

I thought:

“Wait. Was Cioran a fraud? Was he softer than he wanted us to believe?”

I imagined him in our days, like a teenager locked in his room, playing video games, his mom bringing him breakfast, washing his clothes, and then him opening Reddit to post about how meaningless life is.

Is suffering without stakes real? Or just performance? I wanted to go back to the bar and ask those French teachers. But it was late, and I was lost somewhere between crooked alleys of the Latin Quarter.

**

Morning. Headache. Coffee. Train in a few hours. I remembered the fragments of yesterday’s thoughts. One last thing I needed: some evidence that Cioran knew he was not living bravely and just close this whole frustration and continue living my life. And I think I found it. In an interview, late in life, Cioran said:

“I regret having lived so little, having avoided life instead of confronting it. I fled responsibilities, noise, everything that makes a man suffer but also grow.”

“I avoided life.”

“I fled responsibilities.”

“I lived too little.”

I believe he knew that he was not a hero. Not a pure monk. Not a prophet untouched by life. He was a fragile, cowardly witness who still managed to tell the deep truth about despair while living in a quiet agreement with Simone. And nobody could save his mind, even if Simone saved his body or solved his money problems. Somehow, that is enough for me. Not perfect. Not triumphant. But human. And maybe that is all we can ever really expect from anyone.