Written for Ukrainian political journal ‘Nastupna Republica’, 2014

In 1909, the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro published 11 brief theses. These became defining for 20th-century culture as they marked the emergence of a multitude of new artistic movements. Filippo Marinetti called the theses a manifesto, uniting new avant-garde directions under the term “futurism.”

The manifesto declared everything obsolete: “Time and Space died yesterday.” Museums, libraries, and educational institutions were to be demolished. Morality and literary leaders were to be discarded. The hood of a racing car “rushing like shrapnel” was considered a thousand times more beautiful than the statue of Nike of Samothrace. Enthralled by the latest technological achievements, Italian poets and artists began dedicating their works to cars, trains, and electricity. They were characterized by a spirit of defiance and a resolute rejection of past artistic traditions. The futurists’ primary goal was to combat the cultural crisis that had actively spread across Europe since the mid-19th century.

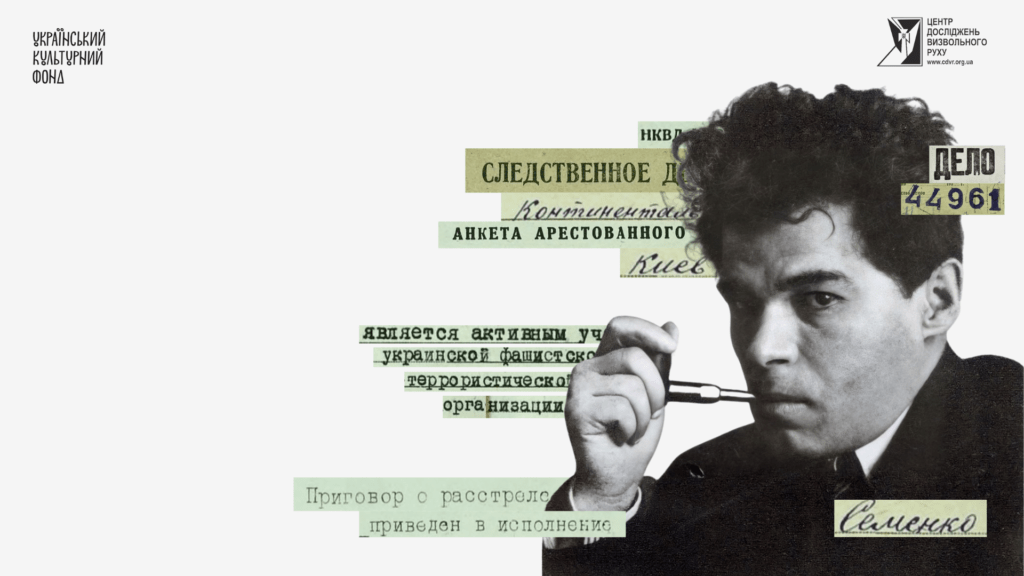

The first signs of this cultural rupture appeared in sculpture and painting, with Impressionism perceived as a manifestation of the crisis. Futurism became a remedy. As Mykhailo Semenko, a prominent representative of the Ukrainian futurist movement, wrote, the directions that “emerged on the corpses of Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist painting, Parnassian and Symbolist poetry” saved the future of art.

At the peak of the futurist movement—especially Ukrainian futurism—in the 1920s, one can feel a heightened tension concerning the death of art, the revision and restoration of the grand cultural narrative. In 1918, Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West appeared, introducing the concept of the cyclical-regressive development of European civilization, which resonated with the ideas of the futurist movement. Issues surrounding scientific and technological progress, Freudianism, tradition, Marxist and Nietzschean discourses, and the boundaries of language all became platforms for confidently shaping a new human being—and thus a new art.

The modernism of futurism lay in its radicalism, aiming to draw public attention to the destruction of the old grand art. As a result, many people avoided the new phenomenon, disliking the dominant “nihilistic element” of the futurist movement. Futurists’ behavior was theatrical and scandalous (“troublemakers!”) to provoke shock. Writing was reduced to total manifestation and relentless simplification (the simpler, the better).

One of the futurists’ main aspirations was to free words from their semantic reference, liberating language from its traditional constraints. Roland Barthes, a significant figure in the study of avant-garde semiotics, noted: “A rebellion against language through language itself inevitably leads to the desire to release the ‘secondary’ language—that is, the deep, ‘non-normative’ energy of the word. Therefore, attempts to destroy language often carry a ceremonial aspect.” Through their spontaneous struggle, futurism created a fundamentally new linguistic world, establishing new principles of lexical and genre innovation.

The European futurist movement became well-known in Ukraine almost from the beginning. Chronological analysis by renowned art researcher V. Vasiutynska-Marcade shows that the cradle of Ukraine’s avant-garde formed more fruitfully than in Russia. It is known that Russian futurism was founded in the village of Chornianka in the Kherson region in 1910 by Ukrainians Vasyl and David Burliuk, who considered themselves descendants of Cossack heritage.

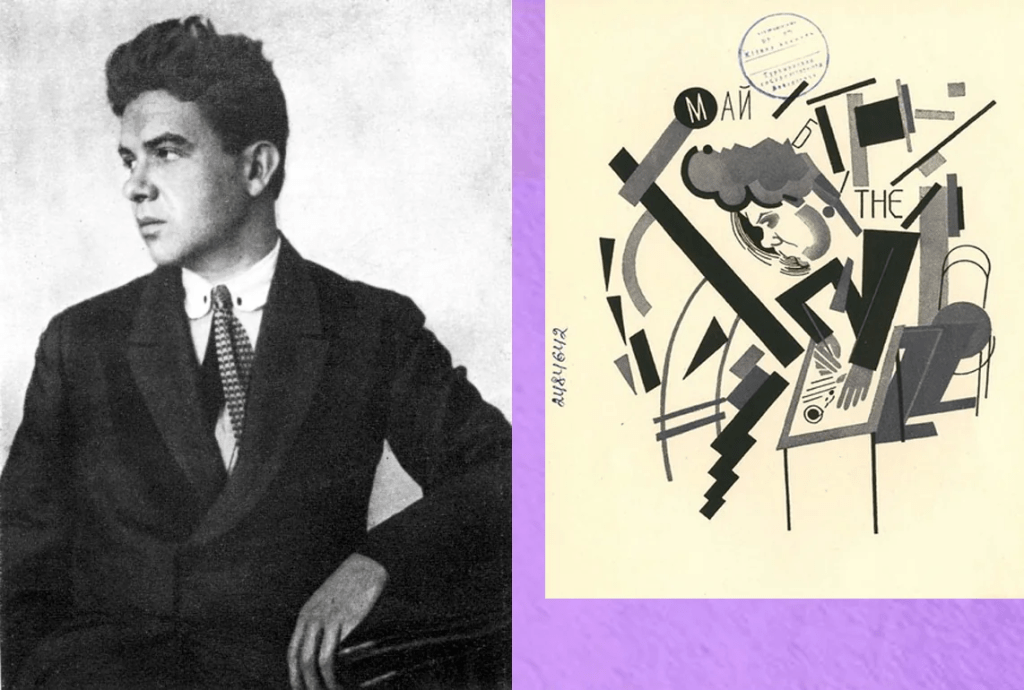

Geo Shkurupii in the 1920s

According to most researchers, Ukrainian futurism emerged during a time when public discourse was burdened by political conventions (the rhetoric of populist logocentrism and the accumulation of modernism). Writers faced the question, “What is the national cultural norm?” To this, futurists added their own question: “Should it even exist?” The birth of Ukrainian futurism was primarily conditioned by a rejection of populism and provincialism, and an acknowledgment of the European cultural model as a foundation.

Futurism in literature began in 1913 with Mykhailo Semenko, and in painting with his brother Vasyl and their friend Pavlo Kovzhun. They established the Quero publishing house (from the Latin quaero—“to seek, to explore”) and transformed their “ordinary” names into Mykhailo, Bazyl, and Pavlo. In 1914, two small books—Daring and Querofuturism—were published, shocking Ukrainian culture, causing confusion, outrage, and total rejection. They dealt a devastating blow to Ukrainian modernism, accustomed to a lofty tone. Daring, which left everyone speechless, contained lines such as:

“You hand me a greasy copy of Kobzar and say: here is my art. Man, I’m ashamed of you… Art is something else entirely. Art must storm, rage, break the shackles of routine. Art must be sharp, daring, and audacious. It should challenge the old and mold the new.”

These provocative lines from Dershannia marked a radical departure from the elevated tone of Ukrainian modernism. Futurism shattered the established artistic norms and forced readers to rethink their understanding of art.

Mykhailo Semenko, as a prominent representative of Ukrainian futurism, firmly rejected the nostalgic attachment to folk traditions and provincialism. Instead, he and his circle advocated for embracing European cultural models and pushing boundaries in literature, visual art, and philosophy.